Enlarge

When Russia began shelling Ukraine in February, ACU alumnus Andrew Kelly (’01) and his wife, Jenny, were 6,000 miles away in Abilene, Texas. But their thoughts immediately flew to 10 orphaned children living at a rescue shelter run by Jeremiah’s Hope, a Ukrainian ministry Andrew founded in 2003 along with fellow ACU graduate Steve Taliaferro (’90).

As news of the war unfolded, the Kellys knew they had to do whatever they could to help.

What followed was a chain of events that reads like an international thriller, involving the Kellys, Taliaferro, former U.S. Navy SEALs, clandestine phone calls, a dangerous convoy through a forest past Russian tanks, and a church in Croatia where Taliaferro now serves as a missionary.

After the harrowing 42-day ordeal, all 10 children made it safely out of the war-torn village of Kolentsi and into a house in Zagreb, Croatia, where they are settling into a new life.

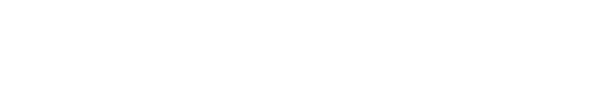

In April, Jenny, who works as administrative coordinator in ACU’s Graduate School of Theology, and Melissa Long, director of the Master of Athletic Training program, traveled to Croatia to meet the newly arrived orphans and help them transition to their new, temporary home.

Enlarge

The children, ranging in age from 5 to 16, arrived in Croatia on a Wednesday. Less than 24 hours later, Jenny and Melissa had flown in and met them. “We wanted to facilitate that first week or so and be extra hands as everyone was trying to settle in,” Jenny explained. “We wanted to help them re-establish a sense of normalcy.”

Jenny, who has a degree in trauma-informed education, used play therapy with the children to help them process what they had been through, while Melissa focused on their physical needs, including taking them to a doctor, outfitting them with clothing and seeing to other health issues.

The children had spent nearly a month hiding out in a farmhouse near the Jeremiah’s Hope compound and then three weeks in a refugee camp in Western Ukraine with little to eat, so they were malnourished when they arrived, Melissa said. “Some of the kids had ear problems, some had skin problems. I was just trying to decipher what the doctor had prescribed and what it was for,” she said. “We did a lot of cooking. We took them shopping for clothes. We took them to McDonald’s, which was a first for some of them.”

Jenny was impressed that the rescue shelter staff was able to help the children feel as safe as they did. “They definitely had trauma; there’s definitely PTSD,” she said. “But over and over again in their play and their descriptions of what happened, they would talk about how Xander [Petrov], our administrator, was protecting them and also how the Ukrainian army was protecting them.”

Seeds of a ministry

The Kellys’ connection with Ukraine began in the mid-1990s when each visited separately on short-term mission teams to work with orphans and other children in a camp setting.

Enlarge

In 2003, Andrew and Steve founded what eventually became known as Jeremiah’s Hope. Steve moved to Donetsk to coordinate an orphanage outreach; Andrew moved to nearby Mariupol to open and operate a transitional living center for post-orphanage graduates. In 2006, Steve moved back to Texas and then on to Zagreb, Croatia, where he serves as a missionary working with the Kušlanova Church of Christ.

Andrew and Jenny met briefly in 2001, reconnected in 2006 and married in 2007. They moved to the village of Kolentsi, halfway between Kyiv and Chernobyl. There, the ministry purchased a piece of land with the vision to build a camp for orphans. The nearly 100-bed camp serves as the base for an outreach into the community called the Sasha Project and houses a rescue shelter for orphaned children and children who have been removed from their homes in crisis situations.

“We’ve spent the last 14 years developing the camp and reaching out into those communities through the Sasha Project,” Andrew said. “We minister to about 70 kids twice a month. We are in their homes, we visit with them, we pray with them, we encourage them, we deliver food packages and school supplies. We walk alongside those families throughout the year and also bring those kids to camp.”

Enlarge

The rescue shelter was developed eight years ago in partnership with the local Ukrainian government and its social services department. “When kids are in crisis and have to be removed from their home, rather than putting them into an orphanage and making them wards of the state, the idea is the government places them with us,” Andrew said. The shelter is on the same property as the camp.

“Over the last eight years we’ve had about 40 kids live with us for various periods of time,” Andrew said. But during the global pandemic that number dwindled.

In February, when Russia invaded Ukraine, only 10 children were living at the rescue shelter. “All happen to be legal-status orphans in that their parental rights have been terminated,” Andrew said.

The Kellys moved to Abilene in June 2021, leaving the orphaned children in the hands of their ministry’s Ukrainian staff. They wanted their five children – including their adopted Ukrainian son who is a senior in high school – to experience life in the U.S. before they headed off to college. Jenny took a job with ACU’s Graduate School of Theology, and Andrew continues to serve as executive director of Jeremiah’s Hope. Since the invasion began, Andrew has been working closely with groups in Abilene to arrange shipping containers of humanitarian aid to send to the war-ravaged country.

Melissa Long connected with the Kellys in 2019, when she took a group of ACU students and alumni to work with Jeremiah’s Hope on a mission trip sponsored by Abilene’s Hillcrest Church of Christ. She joined the ministry’s Board of Directors in 2020. “Some of the kids we worked with in 2019 were still in the rescue shelter, so when we showed up in Croatia, I already knew seven of the 10 children from that previous trip,” she said.

The invasion

On Feb. 24, a 40-mile column of Russian tanks came down through Chernobyl to the town of Ivankiv on their way to Kyiv, about “three miles as the crow flies” from the Jeremiah’s Hope compound, Andrew said. “And that’s where it stalled out. They occupied Ivankiv. They took over the government there,” he said.

Enlarge

Ukrainian forces blew up the bridge over the Teteriv River in Ivankiv as it attempted to prevent the Russian advance. “We had a house mom who couldn’t go home and a local Ukrainian administrator there. So the two of them and our administrator’s girlfriend took care of the kids the first four or five days. Then the house mom’s husband came and got her. So Xander and his girlfriend took care of 10 kids by themselves.”

Xander moved the children off the ministry’s property into a farmhouse to keep them safe. The children alternated between being in the house itself, and when they could hear shelling and bombing, huddling in a 6-by-10-foot root cellar with a dirt floor. “That’s how they survived for about three weeks until we were able to evacuate them,” Andrew said.

The move was fortuitous. The day after they evacuated the camp, Russian soldiers and tanks came into the village, damaged the camp structures and took about 200 packages of humanitarian aid Jeremiah’s Hope had put together for people in the community.

The rescue

Plans to rescue the children began almost immediately, but the Kellys were limited in what they could do from so far away.

Then Andrew came in contact with a group of former Navy SEALs who are now in a private organization “that extracts people from complicated situations,” he said. “A group reached out to me probably about a week into the war. I was told this group wants to hear from you, here’s a number to call.”

Enlarge

He called the number several times and the phone just rang. The final time he called, he heard a beep and a message that said “You know who you are and you know why you’re calling.”

“So I left a message and they called back. It felt very cloak and dagger,” Andrew said. “We were having lunch one day, and a woman called and said, ‘I’m so-and-so. The person you left a message for told me to call. This is who we are, this is what we can do.’

“A day later I got a message, and it was someone who said, ‘We’re going to work through this and we’re going to extract your kids.’ ”

The Kellys spent two weeks communicating with the private rescue group. “They were using satellite technology. I had to send them GPS coordinates of exactly where the house was,” Andrew said. “I had to describe the color of the house, the fence, how many trees were on the property, every last detail I could. Not having been there in a year, I was having to refresh my memory.”

The biggest issue was phone service in Ukraine. “Cell phones were out for the most part. Phone lines were out. Electricity was out at this point. The Internet was out,” Andrew said.

The village is surrounded by a pine forest used by the logging industry. Xander found a freshly cut pile of logs at the far end of the village. By climbing on top, he was able to get one or two bars of service on his cell phone.

“Between myself and these former Navy SEALs, we would set the time for Xander to be back on the pile of logs,” Andrew said. “The logs were in an open field where he was completely exposed. It was also the end of February, and it was still snowing and freezing cold. So he would go out in the dark and stand on this pile, and we would get communication through. The Navy SEAL guys were calling, I was calling, and finally there were two attempts made at extracting them.”

Both attempts failed. The first time the would-be rescuers made it to the village in a car. “But for whatever reason when they got close to the house, they were turned away,” Andrew said. Another time they couldn’t get past the Russian checkpoints.

“Finally, it got to the point where we had to advise Xander, ‘It’s on you. You have to make the decision because you are the one taking the lives of these kids,’ ” Andrew recalled.

Xander told Andrew he would “ask the bread delivery guy how he got through.”

“There was a bread factory an hour away,” Andrew said. “We thought somebody from the bread factory was delivering food to the village.”

Enlarge

Xander discovered it was a man from the village taking his own truck, driving through the forest to get bread on the Ukrainian side of the territory and bringing it back to the village where food was scarce. The American rescue group told him his best option was to coordinate with the driver and follow him out the next time he went to get bread.

The decision was made for the convoy to leave on a Sunday. Andrew talked to the former SEALs the day before, and they said the attempted extraction was a go, although they warned it was “a 50-50 chance whether he’ll make it or not.” That information was communicated to Xander.

“We told him, ‘It’s in your hands. You need to make the decision,’” Andrew said. Xander decided to take the children and leave.

At midnight that Saturday, Andrew got another call from the former SEALs saying, “Pull the plug. Call him and tell him not to go.”

“They couldn’t reach him and I couldn’t reach him,” Andrew said. “The intelligence they had gotten was that the whole road was lined with tanks, and he wasn’t going to make it. We called and called, and we couldn’t get through. It was a long night.”

The Ukrainian van driver led a column of several cars out in the wee hours Sunday morning, and Xander was able to join with two vehicles carrying the kids, Jenny said. They went mostly through the woods. The most dangerous part was crossing a road that Russian tanks routinely traversed.

“Xander told me when he saw the muddy tank tracks on the road, he realized, ‘Oh this could really be it. Any minute a tank could come,’ ” Jenny said. “But they made it across without any problems; they did see some tanks on their way out, but nothing was threatening.”

Xander was supposed to check in when they arrived at the town with the bread factory. It took him almost three hours to make what is normally a one-hour drive, Jenny said. “And so we were waiting and waiting, and finally he called through.” Jenny’s eyes fill with tears as she recalls the moment they got word Xander and the children were safe.

“One night in Croatia he was telling me all this story,” Jenny said, “and he told me that he had basically made his peace. He didn’t think he was going to make it, but he hoped he could get the kids out. So that was tough.”

Narrow misses and close calls

Enlarge

The Kellys see God’s fingerprints all over the children’s rescue.

“When our group evacuated on a Sunday morning and got out past the Russian-occupied area, the very next day, on Monday, the Ukrainian government shut down allowing orphans to cross the border,” Andrew said.

In order to leave, their paperwork had to be lined up perfectly, and to do that they had to have an invitation from Croatia. “Steve and his church in Zagreb rented a house for us, did all the paperwork, made connections with social services, with the local mayor’s office, with the International Red Cross. They already had it lined up to take the kids to the doctor the day they arrived,” he said.

On the day they left the farmhouse, the convoy should have encountered six to eight Russian checkpoints, which had been spotted the day before. But the day they left most were unmanned, Andrew said. They avoided others by going through the forest.

Even an unexpected illness turned into a blessing. The oldest of four siblings at the camp was scheduled to go into a trade school, but he became sick so he was still at the rescue shelter when the evacuation took place.

War through the eyes of a child

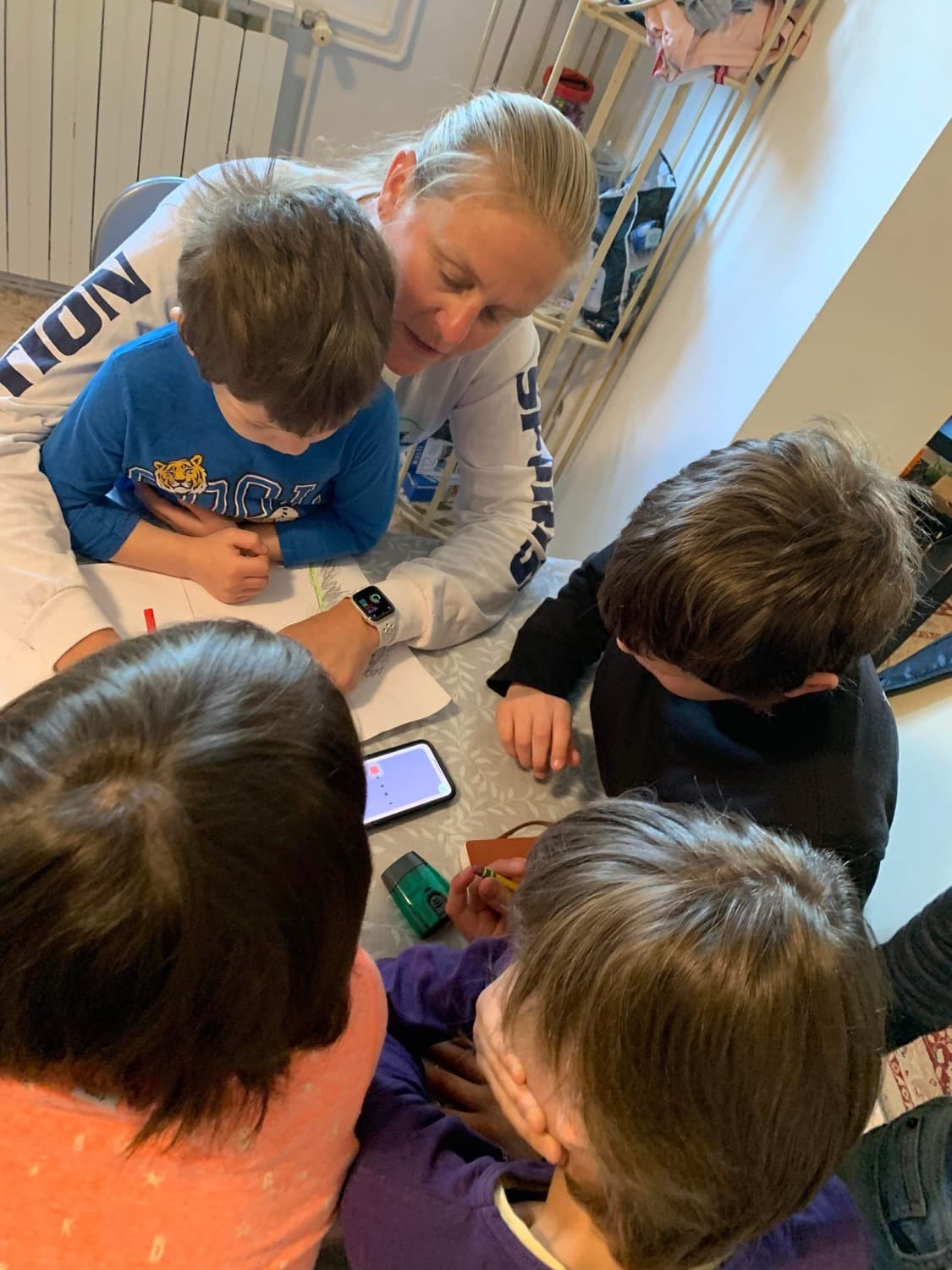

Enlarge

Jenny brought military toys and dollhouse toys to use during play therapy.

One scene constructed by the children shows tanks and military helicopters flanking a house with people inside. “They lined up all the tanks and you can see the house, but if you notice all the dolls are in one room, so they were sheltering,” Jenny said.

“A couple of the girls were worried there was no root cellar in Croatia because what if there was war? It will be memories that will live with them their whole lives, that they will tell their grandkids, but they all did OK and made it through,” she said.

The pictures drawn by the children underscore how deeply their experience impacted them. Many show bombs and mortars coming down on homes, and military tanks and vehicles nearby. But the sketches also illustrate hope. In one drawing, “there’s a guy sitting on the couch and he’s an Army guy, and one of the kids told us that was Xander,” Jenny said. “Even though Xander is not military, they saw him as their protector.”

Reframing the memories

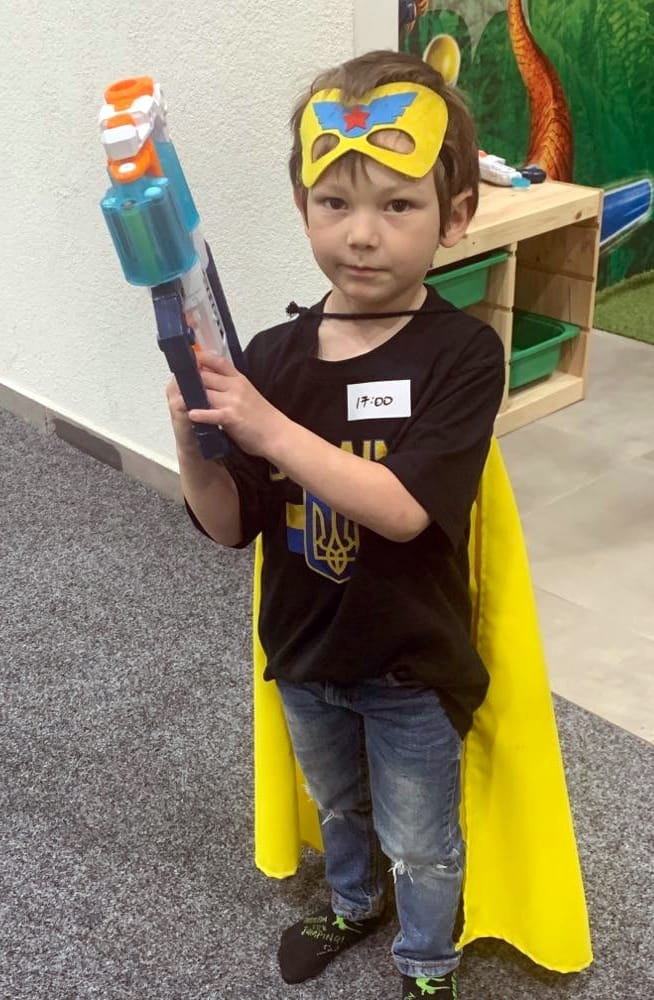

Enlarge

At one point, Jenny asked the children to draw their scariest moment. She then gave each of them a large black crayon and told them, “You’re going to still have that memory, but we can cross out the fear. It’s not anything that needs to scare us anymore because it’s all over.”

They all took the crayons and scribbled out their pictures. “I told them to cover the whole page, so they started to really get into it, and some started giggling. I didn’t prompt them to do this, but some started to rip and crumple their papers. That was really neat. It was like, ‘Yeah, I don’t want this to scare me anymore.’ ”

Though the children are now safe, they and Jeremiah’s Hope have a long road ahead.

“Our Sasha Project ministry is on hold because we can’t get into the villages now. In addition, all of my staff are scattered,” Andrew said. “Our camp cook was one of the people in the village packing humanitarian aid packages when the Russians arrived. She could never get back to Ivankiv. She is still in the village taking care of people there. Our two camp maintenance guys who had built side-by-side with me every building on the property, their home has been destroyed. It’s just rubble. Tanks blew it up and burned it to the ground. They are homeless.

“We have 10 kids in Croatia, no house parents and a PTSD-traumatized administrator trying to take care of them,” he said. “We have one house mom living with them now; she’s also a Ukrainian refugee. Our ministry has been funneling people over there every other week, starting with Melissa and Jenny, just to help keep the kids engaged and active. Ultimately, the kids are orphans and will have to return to Ukraine, but for now Croatia is their new home.”

Even so, “It’s a good place where they’re at,” Jenny said. “God has really put all the pieces in place for them there.”

– Robin Saylor

June 10, 2022