EDITOR’S NOTE: Dr. Charlie Marler (’55), Abilene Christian University professor emeritus of journalism and mass communication, spends a good bit of his retirement time researching the history of his alma mater. One area of particular interest involves the way the lives of students, faculty, staff and alumni were affected by military conflict. On this Memorial Day, he looks back at the three Wildcats who sacrificed their lives during World War I.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dr. Charlie Marler (’55), Abilene Christian University professor emeritus of journalism and mass communication, spends a good bit of his retirement time researching the history of his alma mater. One area of particular interest involves the way the lives of students, faculty, staff and alumni were affected by military conflict. On this Memorial Day, he looks back at the three Wildcats who sacrificed their lives during World War I.

Company A of mainly black soldiers was deployed in defense of the village of Grandlop, France, on Nov. 3, 1918, southeast of Dunkirk close to the Belgian border.

This company of the 1st Battalion, 370th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 93rd Division, had been in France for about six months. Cpl. D.L. Petty (’14) was working in the hospital tent that day, almost 100 years ago.

The morning of Nov. 3, the company’s troops were in a mess line when a cannon shell from the fleeing Crown Prince Wilhelm’s Division exploded among the soldiers. Petty was on duty in the hospital, and he died along with 33 of the black soldiers of his unit, hallowing that French ground just eight days shy of the Armistice.

Today his name, “Lee Petty,” is inscribed on the tablet of the missing at the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery, just below the sill of a stained glass window. Poet Joyce Kilmer also is buried here. The cemetery is close to Fére-en-Terdenois, a commune in the Aisne department of Picardy in northern France.

Two more former ACC students died in military service during World War I, one an Army man and one a Navy man.

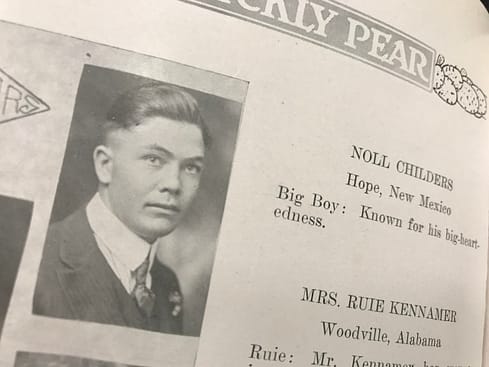

The soldier, Pvt. Isaac Noll Childers, grew up on a Quemado, New Mexico, sheep ranch. He apparently was not related to Col. J.W. Childers for whom ACC was temporarily named Childers Classical Institute. The sailor, Jasper Clifford Miller, was reared in Abilene.

Noll, nicknamed “Bigun” and “Tamales,” was a big-hearted 190-pounder. “All ACC students will be glad to see ‘Tamales’ on the football team next year,” according to the 1918 Prickly Pear. “His hard passes were always right on the mark.”

But the U.S. entry into World War I in 1918 and the Spanish influenza pandemic changed Childers’ fate. He registered for the draft Sept. 7, 1918, in his hometown of Quemado, transferred to New Mexico A&M College and joined its Student Army Training Corps. On Oct. 20, Noll died in training camp in the prime of his life, stricken down by this lethal Spanish influenza fever, which took the lives of 30,000 other Army trainees. At Camp Cody in Deming, for instance, 181 died in that October timeframe – and 6,266 nationally.

Blanket bans on public meetings were common during the epidemic, including funerals. The rate of deaths overwhelmed undertakers, grave diggers and coffin suppliers. Because of these conditions, the place of Noll’s burial is unknown today. Perhaps he lies in an isolated grave on a ranch or even in a group grave as was common during the epidemic.

Earlier in the year, gunner’s mate third class Miller was aboard the USS Cyclops, a behemoth coal collier designed to transport coal to warships. He had transferred to the Baltimore-bound Cyclops as a passenger at Rio de Janerio to return to the U.S. after sea duty with his brother, Virgil, another ACC student. The 520-foot-long Cyclops, which operated in the Atlantic Ocean, left Rio on Feb. 14, 1918.

En route north, the unlikely named collier, already crippled by one out-of-commission engine, encountered a storm in the infamous Bermuda Triangle after leaving Bridgetown, Barbados. Apparently, its overloaded cargo of 11,000 tons of manganese ore for munitions shifted and the Cyclops went down in the storm on or about March 4 with the loss of all 307 aboard, including Miller.

He became the first Abilenian lost during World War I, making his mother, Hattie Rhodes Miller, the first Gold Star mother of Abilene and ACC. She was the aunt, and Jasper the cousin, of 1957 graduate A.L. “Dusty” Rhodes. Jasper had enlisted in the Navy in Dallas June 15, 1915.

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt declared the Cyclops to be officially lost June 1, 1918, and the date of death of Miller and the others was declared as June 14, 1918. A digital cemetery, including a clipping and photo of Miller, is located at findagrave.com/virtual-cemetery/411201. In Baltimore, Cyclops’ unreached destination, its crew and passenger names are inscribed in marble on the War Memorial.

The Cyclops remains one of the greatest mysteries in the history of the U.S. Navy, its greatest non-combat loss ever. “The Navy did its best to locate the vessel,” according to a 2011 article in The Virginian Pilot. The only sign ever found of the Cyclops is a small wooden chest now in the Mariner’s Museum in Newport News, identified by the ship’s name stenciled on it. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson said, “Only God and the sea know what happened to the great ship.”

On Nov. 11, 1918, the ACC campus experienced an “outburst of joy” with “the news that fighting had ceased and the great war was over,” according to the Prickly Pear. On Armistice Day 1919 the college engaged in a full day of thanksgiving led by ACC president Jesse P. Sewell, who recognized “Our Boys Who Returned” and “The Boys Who Never Came Back” – D.L. Petty, Noll Childers and Jasper Miller. None of them lie in a marked grave, but their alma mater will never forget them.

WRITER’S NOTE: My wife, Peggy (Gambill ’55), and I were stationed in Germany in 1957 and later made four trips to Europe. If only we had known then what recent research has revealed, we would have made a pilgrimage to the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery in northern France and lingered a long time beneath the stained glass window sill and Lee Petty’s name. Students and alumni who visit Europe in the future would do well to put a visit to Oise-Aisne on their bucket lists. Likewise, with the Baltimore War memorial.

SHARE: [Sassy_Social_Share

type="standard"]