Garner Roberts (’70) is a freelance writer who retired from ACU in 2004 after a distinguished career as a writer, editor, sports information director and media relations professional. He is a member of the College Sports Information Directors Association Hall of Fame and the ACU Sports Hall of Fame. This profile of the late Bobby Morrow (’58) is adapted from The ACU Century, the university’s history book published in 2005 during its Centennial.

The summer games of the XVI Olympiad in Melbourne, a handsome city beside a bright blue bay on the southeast coast of Australia, were the first to be chronicled by Sports Illustrated.

The popular new magazine, which made its debut Aug. 16, 1954, had selected as the first two recipients of its Sportsman of the Year award British runner Roger Bannister, who became history’s first sub-four-minute miler when he ran 3:59.4 in Oxford, England, on June 5, 1954, and American baseball player Johnny Podres, who pitched the Dodgers to triumph over the Yankees in the 1955 World Series.

In 1956, in addition to the usual list of candidates for the prestigious prize, there were heroes from the Olympic games. Indeed, 1956 was a year of glittering performances and great moments. Mickey Mantle, a 25-year-old outfielder for the Yankees, dominated headlines by hitting 52 home runs, and teammate Don Larsen pitched a perfect game in the World Series. Twenty-one-year-old Floyd Patterson became boxing’s youngest heavyweight champion, and golfer Cary Middlecoff won his second U.S. Open Championship. Paul Hornung of Notre Dame was the college football star, and Frank Gifford of the New York Giants was pro football’s outstanding player. At the Olympic Games in Melbourne, the United States men’s track and field team earned 15 gold medals and a total of 28 gold, silver and bronze – two standards the 12 succeeding teams have failed to reach.

Who would the editors of Sports Illustrated pick as Sportsman of the Year for 1956?

Bobby Joe Morrow of San Benito, Texas, the sophomore sprint sensation from Abilene Christian College.

In the sum of about 41 seconds, Morrow (’58) decorated himself with three gold medals and “earned clear title to the accolade: Sportsman of the Year for 1956.” He became the first man since Jesse Owens to outrun the world’s best sprinters to the finish line in both the Olympic 100 meters and 200 meters, and he linked with three of his U.S. teammates to smash the world record in the 400-meter relay. One writer said Morrow ran “like a scalded cat.” Paul O’Neil, writing in Sports Illustrated Jan. 7, 1957, was quick to add, “Athletic prowess was not the sole reason for Bobby Morrow’s selection, although it was an important factor indeed in a year so notable for excellence in sport. His multiple victories, gratifying though they may have been to his countrymen, could hardly have qualified him for the honor if they had not also served to dramatize the spirit as well as the accomplishments of the Olympic movement.

“But Bobby Morrow the unusual sprinter is also an unusual young man, and none symbolized more eloquently than he the ideals of sportsmanship which the athletes of the U.S. Olympic team took with them to Australia.”

That men’s track and field team the U.S. sent to Melbourne certainly was one of the very best in history. In addition to the newly crowned World’s Fastest Man, the roster featured the first person to high jump 7 feet (Charles Dumas), the first man to reach 60 feet in the shot put (Parry O’Brien), the only man to repeat as Olympic pole vault champion (Bob Richards), and the only man to win four gold medals in one event (discus thrower Al Oerter). The U.S. men dominated the competition by winning 15 of the 24 events.

It was Morrow’s performance that most fascinated fans. “I was standing near the finish line for the 100-meter final,” Richards said. “The track was terrible. Loose, like sawdust, and Bobby was kicking cinders 10 feet into the air behind him. On a modern surface, there is no doubt in my mind that Bobby would have run an eight-something 100 meters. He was the greatest sprinter I ever saw.”

A humble but not self-effacing young man, Morrow simply attributed his success to “being so perfectly relaxed that I can feel my jaw muscles wiggle.”

* * *

Morrow learned to run relaxed from his coach in Abilene, Oliver Jackson (’42). The Wildcats’ track and field mentor, who was building a dynasty at Abilene Christian even before Morrow arrived in September 1954, first saw Morrow run as a high school junior. “Bobby is a born sprinter,” Jackson told reporters. “All you had to do was take one look at him even as a junior in high school, and you couldn’t miss it. He’s big (6 feet 1.5 inches, 175 pounds). He has long legs. He’s got terrific power in his thighs, and he’s got leg speed as well as a big stride.

“He runs right,” Jackson added. “He leans a little and pushes the ground back rather than reaching out and putting extra strain on his legs. I’m certain that’s one reason he doesn’t get hurt. He’s tough, too, a strong man. He’s a great competitor. He hates to lose.”

Bobby Joe Morrow was born Oct. 15, 1935, in Rangerville in south Texas’ Rio Grande Valley. His parents, Bob Floyd and Lucille Morrow, lived in a simple, white clapboard house and owned and operated a 600-acre cotton and carrot farm in the hot border country. Bobby helped his father on the farm, fished in the bays of the Gulf of Mexico, and hunted deer and javelina in the rough backcountry. He drank fresh orange juice and brought frog legs home for Lucille to fry.

He started his athletics career as a running back at San Benito High School for coach Jim Barnes’ Greyhound football team. “When I got around the end,” Morrow remembers, “nobody could catch me.”

Morrow added track and field to his busy schedule as a sophomore in the spring of 1952. “They saw I had speed so they wanted me to go out for track,” he said. They built starting blocks in the school shop, and Bob Floyd drove his tractor to school before afternoon practice to level and smooth the dirt track.

Under the guidance of coach Jake Watson, Morrow qualified for the state meet as a sophomore, then won the 100 as a junior and the 100 and 220 as a senior. “It was a great experience for me just to be in Austin,” Morrow added. “Going to the state meet from our little high school in San Benito was something.”

Morrow lost only four races as a junior and was undefeated as a senior, but college originally wasn’t in his plans. “I wasn’t planning to go to college,” he said. “I was going to stay home and farm with my Dad. I didn’t prepare my studies and grades to go to college. I had to go to summer school to get the credits I needed to qualify.”

Because of the influence of his parents, coaches Jackson and Watson, and his brother Gordon (’54), who was already a student at ACC with several cousins, Morrow declined offers from each Southwest Conference member and other universities to enroll at Abilene Christian. “I had made up my mind to go to school in Abilene because of Oliver Jackson and the great coach that he was and because of my Christian upbringing,” he said. “That’s where I wanted to be. I knew what kind of school it was, I knew what kind of man he was, and I knew what kind of environment it was going to be.”

As a 19-year-old college freshman, Morrow blossomed. He learned from Jackson the proper way to start (“I was a terrible starter in high school”) and how to relax. Jackson explained, “In high school he didn’t drive out. He’d just sort of stand up and start running. He didn’t relax enough. His arms were wrong. He carried his elbows out wide and tightened up at the end of races.”

Morrow learned to run with his lips slightly parted to prevent clenched jaws and strained shoulders and arms. As Sports Illustrated explained it, “a man must run his hardest, but must hold back the natural tensions of combat.”

“Bobby was the easiest guy to coach you ever saw,” Jackson said. “He was the type of guy we needed here in our program. He was so dedicated to winning that he would pay the price. We told Bobby he could be the Olympic champion, but it’s going to take a lot of work, but he was willing to do it. I never heard Bobby fuss or argue about the workouts.”

He won the 100-yard dash as the Texas Relays in his fifth race of the 1955 season and June 4 in Abilene clocked his famous wind-aided 9.1 seconds in the 100 as Jackson’s Wildcats won their third NAIA collegiate championship.

Three weeks later he was the AAU national champion in the 100 the day before his 34-race winning streak ended with a rare loss in the AAU 220.

“Bobby had poise and a fluid motion like nothing I’ve ever seen,” Jackson said. “He could run a 220 with a rootbeer float on his head and never spill a drop. I made an adjustment to his start when he was a freshman. After that, my only advice to him was to change his major to speech because he’d be destined to make a bunch of them.”

As a sophomore in 1956 Morrow established himself as the Olympic favorite by losing only once (in the Drake Relays 100 to Duke’s Dave Sime) in 34 finals, matching the world record three times in the 100 (10.2) and twice in the 200 (20.6), winning NAIA and NCAA Division I collegiate titles, and claiming his spot on the Olympic team by speeding to victories in the 100 and 200 dashes at the Olympic Trials in Los Angeles.

Longtime Baylor University coach Jack Patterson told Track and Field News that Morrow “has great desire and determination and concentration. He’s willing to make sacrifices to attain any goal he has in mind. There are a lot of sprinters capable of running just as fast as Bobby. But when he lines up against them he just ties them in knots.”

The rival coach continued, “Bobby doesn’t look like a sprinter. To me, Dave Sime of Duke is much more like you expect a sprinter to be – high strung, temperamental and jittery. Sime is the race horse, Morrow the even-tempered, unexcited plow horse.”

Jackson added, “You couldn’t ever tell what Bobby was going to say or do because he was very quiet and didn’t say much. He was not a real enthusiastic type of guy – except when the gun fired. He was pretty enthusiastic when the gun fired.”

The U.S. team boarded a plane in Los Angeles for the 48-hour ride to Australia that included stops in Hawaii, the Canton Islands and the Fiji Islands. Morrow and his U.S. teammates arrived early to recover from the trip (“It took a long time to get over that plane ride”), get acclimated and practice baton handoffs for the relay.

He and roommate Glenn Davis, 22-year-old hurdler from Ohio State, made their home in the Olympic village among the other 3,300 athletes and talked about their upcoming events (Davis also won a gold medal in the 400 hurdles the same day Morrow won the 100). “Having someone to talk to helped me put up with the pressure,” Morrow said. “We talked about relaxing, running our own race and not worrying about the others.”

Jackson also traveled to Melbourne and met Morrow each day at practice. “I always looked forward to seeing coach Jackson,” Morrow said. “It was uplifting for me to see him every day. I was a kid among strangers. It was a relief to me to have him there.”

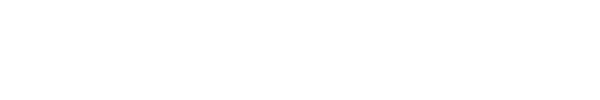

The games opened Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 22, 1956. The next day Morrow, running in the last of 12 qualifying heats, ran the fastest time (10.4) of the first round and improved to 10.3 in the quarterfinals. On Saturday, Nov. 24, he rode a bus to the stadium, and two hours after winning his semifinal heat with another Olympic record 10.3, he settled into the blocks for the Olympic 100 final.

“I tried not to get distracted,” he remembers, “to mind my own business, put my blocks down and do what I came to do. I knew I had to get a good start. I was usually a slow starter and had to make up the difference. I think I came out about even, but I could see midway through the race I had to pick it up a little bit.”

He and veteran teammate Thane Baker overtook early leader Hector Hogan of Australia, with Morrow winning in 10.5 before a standing-room-only crowd of more than 110,000 people at Melbourne’s Cricket Grounds. “After the 100 was completed, I relaxed more,” Morrow said. “I felt better about the 200. I liked to run the curve.”

Morrow rested on Sunday then ran the first two rounds of the 200 on Monday before the semifinals and final on Tuesday, Nov. 27. Baker beat Morrow, nursing a slight groin strain from the 100, in the first semifinal. In the final, three Americans, including defending champion Andy Stanfield, came off the curve running together in front. Morrow shot to the lead and easily took his second gold medal with his sixth world record (20.6) of the year.

After quarterfinals and semifinals in the 400 relay, Morrow’s 11-race Olympic experience ended Dec. 1 with another world record. Ira Murchison, Leamon King, Baker and Morrow carried the baton around the track in 39.5 seconds.

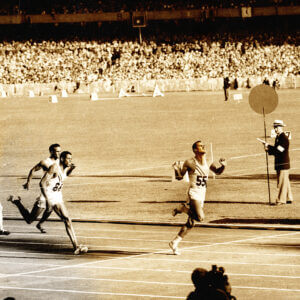

Morrow returned to a hero’s welcome in Los Angeles and Abilene. “Flying into the Abilene airport I could see the cars and the people and my teammates lined up to greet me,” he said. “I didn’t know what was going on. It wasn’t until then that it all really struck home to me what I did over there …

“I certainly appreciated all the help and encouragement I got from the student body,” Morrow continued. “I loved the school, loved all the people there and loved to compete for the school. It’s a great school. I enjoyed every moment at ACC.”

In addition to his Sportsman of the Year award from Sports Illustrated, Morrow received the Sullivan Award from the AAU as amateur athlete of the year, appeared several times on national television and on the covers of Life and Sport magazines, addressed a joint session of the Texas legislature, and was named one of the nine “Greatest Living Americans” by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

He lost only once as a junior in 1957 and added four more collegiate titles in the 100 and 220 at the NAIA and NCAA Division I championships. Morrow completed his Wildcat career as a senior June 21, 1958, by winning the AAU 100 and 220, giving him 80 victories in 88 collegiate races. “He had the most phenomenal career I guess that a sprinter has ever had,” Jackson said.

Among his many other honors are selections to the U.S. Track and Field Hall of Fame, the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame, the Texas Sports Hall of Fame, and the ACU Sports Hall of Fame. He donated his three gold medals to the Smithsonian Institution, Texas Sports Hall of Fame and ACU.

* * *

In 1956, the year Abilene Christian arrived at the midpoint of its first century, every American could want to be Bobby Morrow, a likeable, handsome young man with three Olympic gold medals around his neck and tenacity of purpose in his heart. And every American could admire Oliver Jackson, a cheerful, emulous 36-year-old coach with a rare grasp of the subtleties required to help a runner reach his peak.

Writing about Morrow after a trip to Abilene, Harold Ratliff of The Associated Press reported, “There probably are 65,000 people, the entire population of Abilene, who think Bobby Morrow is the greatest guy in the world as well as the greatest runner. It is difficult to picture in words what Morrow means to the people here. They never mention Bobby’s feats in sport without pointing out that he’s the kind of man who should be the ideal of every American boy.”

O’Neil described Morrow in Sports Illustrated as “the sort of Texan which most of the U.S., the sort of American which most of the world has had too little opportunity to know.”

Jackson said Morrow was “strong character. He didn’t ever try to take credit for the winning that we had. He always talked about the other guys on the relay. Bobby was always complimenting them. After the race they would hug each other. It was a real team effort.”

Many of the 2,000 students enrolled at ACC in the mid-1950s shared in the team effort; 1,009 students and 70 faculty members signed a telegram sent to Morrow in Melbourne. Members of the U.S. team visited Morrow’s room in the Olympic village to marvel at the seven-foot-long telegram. “I wish I could go to a school like that,” many of them said.

Morrow never denied an autograph to a fan (he still gets about a dozen letters a month from around the world), and he is quick to give credit to Jackson. “Without this man,” he said, “three gold medals would not have been possible. He is the greatest track coach in the world.”

When Jackson was inducted into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame Dec. 29, 1978, in Dallas, Morrow called his coach “the co-holder of three gold medals.” He added, “I’ve received a lot of high honors in my life, but this is the greatest, inducting Oliver Jackson into the Hall of Fame. We’ve traveled many miles together, we’ve shared some wins, and we’ve also shared some losses. He wasn’t only a coach, but a friend. He was concerned with how you participated on the track, but he was more concerned with how you conducted yourself off the track.”

* * *

There were men who came before Oliver Jackson and Bobby Morrow, such as coaches A.B. Morris, J. Eddie Weems and Arthur “Tonto” Coleman (’28), and those who came after, such as 1972 Olympic coach Bill McClure (’48). They combined to build what Texas Monthly called in December 1999 the state’s Sports Dynasty of the Century.

Three other Wildcats – Earl Young (’62), Albert Lawrence (’85) and Greg Meghoo (’89) – were Olympic medalists, including Young’s gold for the U.S. in 1960. Billy Pemelton (’64), Tim Bright (’83), Billy Olson (’81), Mark Witherspoon (’85) and Eric Thomas (’99) have been U.S. Olympians, led by Bright’s three appearances. Dyle Vaughn (’30) was a finalist at the NCAA championships as early as 1929, Elmer Gray (’32) competed in the U.S. Olympic Trials as far back as 1932, and Howard Green (’35) represented America in international competition as early as 1934.

Jackson, Don Hood (’55), Wes Kittley (’81) and Jon Murray have coached the Wildcats to a total of 53 men’s and women’s collegiate team titles in NAIA and NCAA Division II. Morrow, Freddie Williams (’87), John Lawler (’63), Cliff Felkins (’88) and Mazel (Thomas ’90) Tatham have been NCAA Division I individual champions. There have been a multitude of world records, and student-athletes have competed on six continents in meets such as the World Championships, World Cup, Goodwill Games, World University Games and Pan American Games.

“I’ve always been maybe a little too highly competitive,” Jackson said. “There’s only one place, as far as I’m concerned, and that’s on the victory stand. We always pushed hard to be the best in everything we could.”

“If the school finds expression in the Bible,” O’Neil so aptly wrote in Sports Illustrated, “it also finds expression in going forth to conquer in athletics.”

Related Morrow coverage

- Time, Life, SI: Wildcats have covered them all

- Olympic Diary: ACU’s ‘Texas Sports Dynasty’

- Olympic Diary: Politics, sport often mix

- Olympic Diary: The wide world of ACU sports

- Saturday’s meet the biggest at ACU in 55 years

- ACU Remembers: Bill Woodhouse

- ACU Remembers: Waymond Griggs

- ACU Remembers: Bobby Morrow